NEWS AIRobotics

Imagine taking a time machine back to 1750—a time when the world was in a permanent power outage, long-distance communication meant either yelling loudly or firing a cannon in the air, and all transportation ran on hay. When you get there, you retrieve a dude, bring him to 2015, and then walk him around and watch him react to everything.

It's impossible for us to understand what it would be like for him to see shiny capsules racing by on a highway, talk to people who had been on the other side of the ocean earlier in the day, watch sports that were being played 1,000 miles away, hear a musical performance that happened 50 years ago, and play with my magical wizard rectangle that he could use to capture a real-life image or record a living moment, generate a map with a paranormal moving blue dot that shows him where he is, look at someone's face and chat with them even though they're on the other side of the country, and worlds of other inconceivable sorcery. This is all before you show him the internet or explain things like the International Space Station, the Large Hadron Collider, nuclear weapons, or general relativity.

This experience for him wouldn't be surprising or shocking or even mind-blowing—those words aren't big enough. He might actually die.

No, in order for the 1750 guy to have as much fun as we had with him, he'd have to go much farther back—maybe all the way back to about 12,000 BC, before the First Agricultural Revolution gave rise to the first cities and to the concept of civilization. If someone from a purely hunter-gatherer world—from a time when humans were, more or less, just another animal species—saw the vast human empires of 1750 with their towering churches, their ocean-crossing ships, their concept of being "inside," and their enormous mountain of collective, accumulated human knowledge and discovery—he'd likely die.

And then what if, after dying, he got jealous and wanted to do the same thing. If he went back 12,000 years to 24,000 BC and got a guy and brought him to 12,000 BC, he'd show the guy everything and the guy would be like, "Okay what's your point who cares." For the 12,000 BC guy to have the same fun, he'd have to go back over 100,000 years and get someone he could show fire and language to for the first time.

In order for someone to be transported into the future and die from the level of shock they'd experience, they have to go enough years ahead that a "die level of progress," or a Die Progress Unit (DPU) has been achieved. So a DPU took over 100,000 years in hunter-gatherer times, but at the post-Agricultural Revolution rate, it only took about 12,000 years. The post-Industrial Revolution world has moved so quickly that a 1750 person only needs to go forward a couple hundred years for a DPU to have happened.

This pattern—human progress moving quicker and quicker as time goes on—is what futurist Ray Kurzweil calls human history's Law of Accelerating Returns. This happens because more advanced societies have the ability to progress at a faster rate than less advanced societies—because they're more advanced. 19th century humanity knew more and had better technology than 15th century humanity, so it's no surprise that humanity made far more advances in the 19th century than in the 15th century—15th century humanity was no match for 19th century humanity.

This works on smaller scales too. The movie Back to the Future came out in 1985, and "the past" took place in 1955. In the movie, when Michael J. Fox went back to 1955, he was caught off-guard by the newness of TVs, the prices of soda, the lack of love for shrill electric guitar, and the variation in slang. It was a different world, yes—but if the movie were made today and the past took place in 1985, the movie could have had much more fun with much bigger differences. The character would be in a time before personal computers, internet, or cell phones—today's Marty McFly, a teenager born in the late 90s, would be much more out of place in 1985 than the movie's Marty McFly was in 1955.

This is for the same reason we just discussed—the Law of Accelerating Returns. The average rate of advancement between 1985 and 2015 was higher than the rate between 1955 and 1985—because the former was a more advanced world—so much more change happened in the most recent 30 years than in the prior 30.

So—advances are getting bigger and bigger and happening more and more quickly. This suggests some pretty intense things about our future, right?

Kurzweil suggests that the progress of the entire 20th century would have been achieved in only 20 years at the rate of advancement in the year 2000—in other words, by 2000, the rate of progress was five times faster than the average rate of progress during the 20th century. He believes another 20th century's worth of progress happened between 2000 and 2014 and that another 20th century's worth of progress will happen by 2021, in only seven years. A couple decades later, he believes a 20th century's worth of progress will happen multiple times in the same year, and even later, in less than one month. All in all, because of the Law of Accelerating Returns, Kurzweil believes that the 21st century will achieve 1,000 times the progress of the 20th century.

If Kurzweil and others who agree with him are correct, then we may be as blown away by 2030 as our 1750 guy was by 2015—i.e. the next DPU might only take a couple decades—and the world in 2050 might be so vastly different than today's world that we would barely recognize it.

This isn't science fiction. It's what many scientists smarter and more knowledgeable than you or I firmly believe—and if you look at history, it's what we should logically predict.

So then why, when you hear me say something like "the world 35 years from now might be totally unrecognizable," are you thinking, "Cool….but nahhhhhhh"? Three reasons we're skeptical of outlandish forecasts of the future:

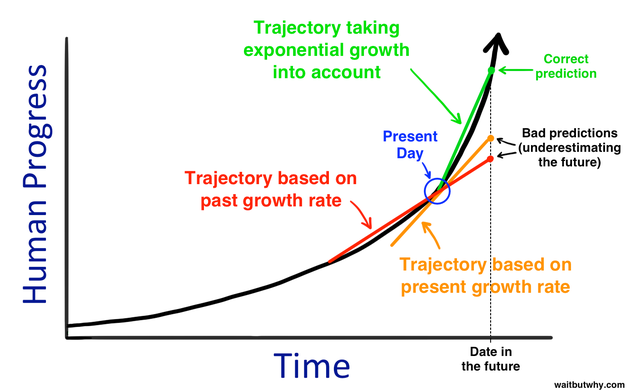

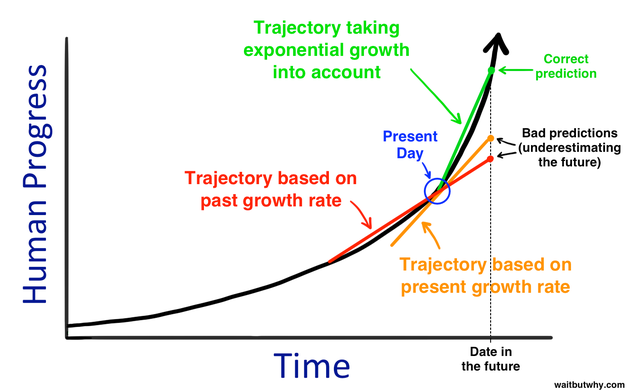

It's most intuitive for us to think linearly, when we should be thinkingexponentially. If someone is being more clever about it, they might predict the advances of the next 30 years not by looking at the previous 30 years, but by taking thecurrent rate of progress and judging based on that. They'd be more accurate, but still way off. In order to think about the future correctly, you need to imagine things moving at a much faster rate than they're moving now.

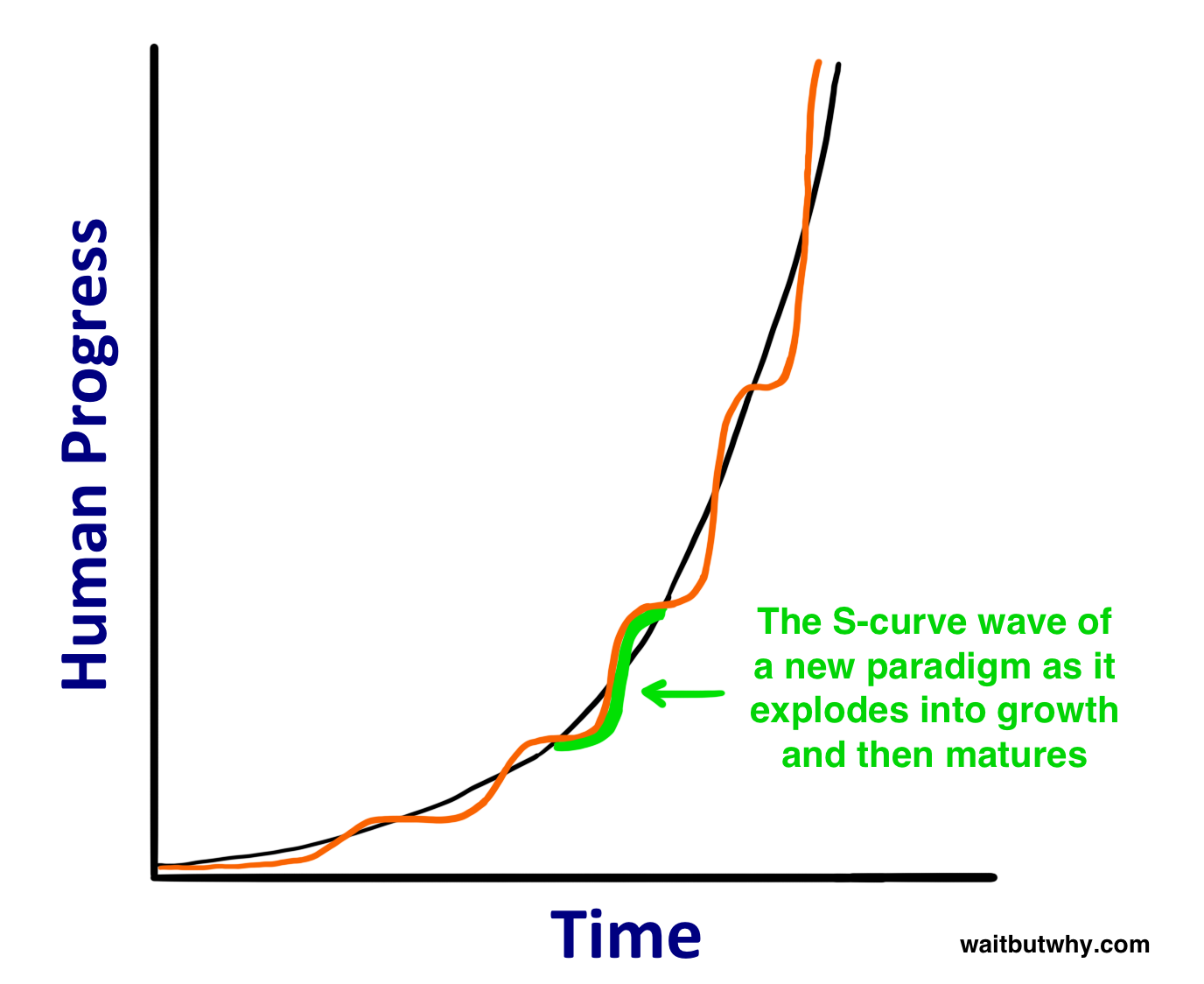

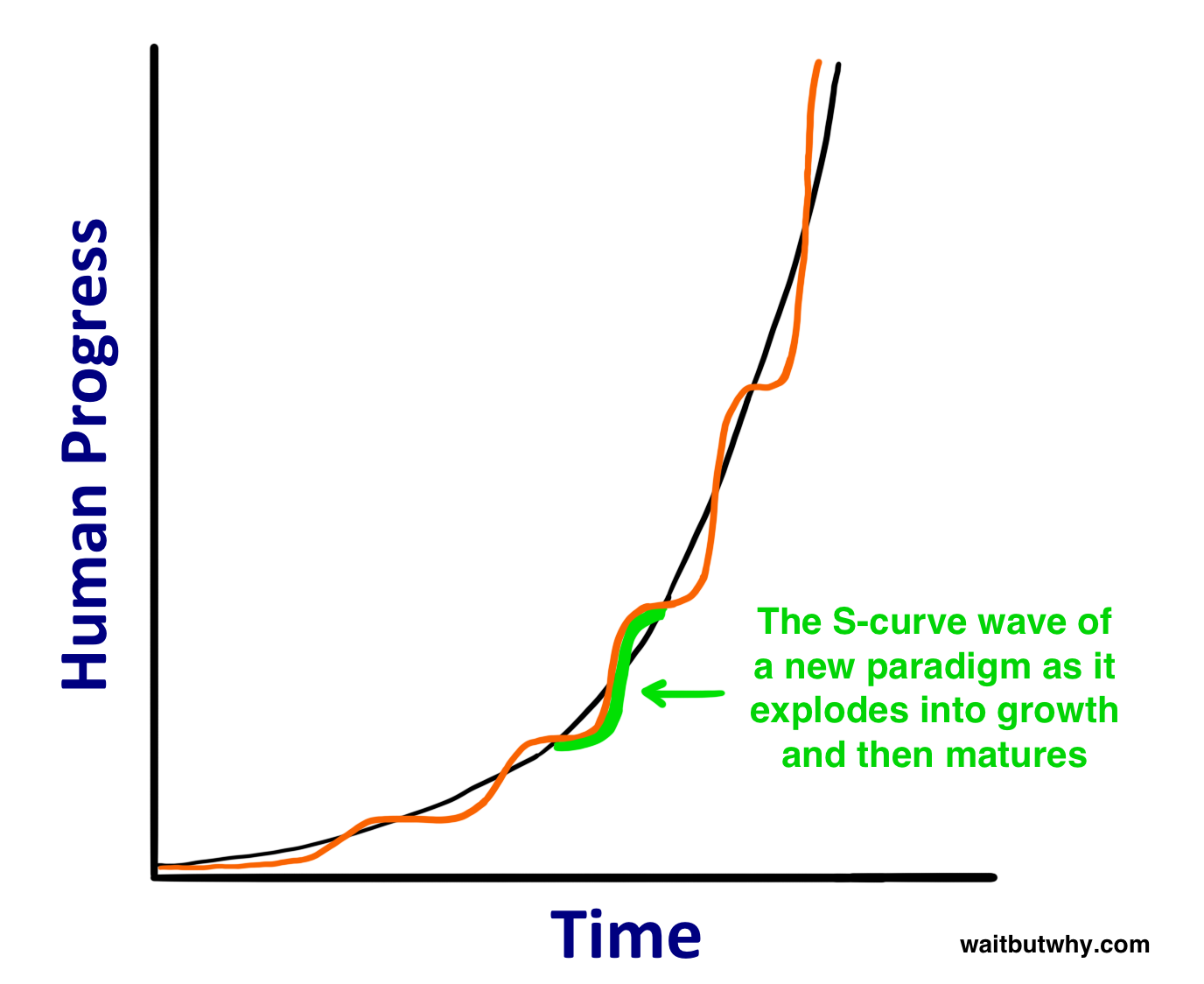

An S is created by the wave of progress when a new paradigm sweeps the world. The curve goes through three phases:

An S is created by the wave of progress when a new paradigm sweeps the world. The curve goes through three phases:

1).Slow growth (the early phase of exponential growth)

2).Rapid growth (the late, explosive phase of exponential growth)

3).A leveling off as the particular paradigm matures.

If you look only at very recent history, the part of the S-curve you're on at the moment can obscure your perception of how fast things are advancing. The chunk of time between 1995 and 2007 saw the explosion of the internet, the introduction of Microsoft, Google, and Facebook into the public consciousness, the birth of social networking, and the introduction of cell phones and then smart phones.

That was Phase 2: the growth spurt part of the S. But 2008 to 2015 has been less groundbreaking, at least on the technological front. Someone thinking about the future today might examine the last few years to gauge the current rate of advancement, but that's missing the bigger picture. In fact, a new, huge Phase 2 growth spurt might be brewing right now.

We base our ideas about the world on our personal experience, and that experience has ingrained the rate of growth of the recent past in our heads as "the way things happen." We're also limited by our imagination, which takes our experience and uses it to conjure future predictions—but often, what we know simply doesn't give us the tools to think accurately about the future. (Kurzweil points out that his phone is about a millionth the size of, a millionth the price of, and a thousand times more powerful than his MIT computer was 40 years ago. Good luck trying to figure out where a comparable future advancement in computing would leave us, let alone one far, far more extreme, since the progress grows exponentially.)

When we hear a prediction about the future that contradicts our experience-based notion ofhow things work, our instinct is that the prediction must be naive. If I tell you, later in this post, that you may live to be 150, or 250, or not die at all, your instinct will be, "That's stupid—if there's one thing I know from history, it's that everybody dies." And yes, no one in the past has not died. But no one flew airplanes before airplanes were invented either.

So while nahhhhh might feel right as you read this post, it's probably actually wrong. The fact is, if we're being truly logical and expecting historical patterns to continue, we should conclude that much, much, much more should change in the coming decades than we intuitively expect. Logic also suggests that if the most advanced species on a planet keeps making larger and larger leaps forward at an ever-faster rate, at some point, they'll make a leap so great that it completely alters life as they know it and the perception they have of what it means to be a human—kind of like how evolution kept making great leaps toward intelligence until finally it made such a large leap to the human being that it completely altered what it meant for any creature to live on planet Earth.

And if you spend some time reading about what's going on today in science and technology, you start to see a lot of signs quietly hinting that life as we know it cannot withstand the leap that's coming next.

There are three reasons a lot of people are confused about the term AI:

1) We associate AI with movies. Star Wars. Terminator. 2001: A Space Odyssey. Even the Jetsons. And those are fiction, as are the robot characters. So it makes AI sound a little fictional to us.

2) AI is a broad topic. It ranges from your phone's calculator to self-driving cars to something in the future that might change the world dramatically. AI refers to all of these things, which is confusing.

3) We use AI all the time in our daily lives, but we often don't realize it's AI. John McCarthy, who coined the term "Artificial Intelligence" in 1956, complained that "as soon as it works, no one calls it AI anymore." Because of this phenomenon, AI often sounds like a mythical future prediction more than a reality. At the same time, it makes it sound like a pop concept from the past that never came to fruition. Ray Kurzweil says he hears people say that AI withered in the 1980s, which he compares to "insisting that the Internet died in the dot-com bust of the early 2000s."

So let's clear things up. First, stop thinking of robots. A robot is a container for AI, sometimes mimicking the human form, sometimes not—but the AI itself is the computer inside the robot. AI is the brain, and the robot is its body—if it even has a body. For example, the software and data behind Siri is AI, the woman's voice we hear is a personification of that AI, and there's no robot involved at all.

Secondly, you've probably heard the term "singularity" or "technological singularity." This term has been used in math to describe an asymptote-like situation where normal rules no longer apply. It's been used in physics to describe a phenomenon like an infinitely small, dense black hole or the point we were all squished into right before the Big Bang. Again, situations where the usual rules don't apply. In 1993, Vernor Vinge wrote a famous essay in which he applied the term to the moment in the future when our technology's intelligence exceeds our own—a moment for him when life as we know it will be forever changed and normal rules will no longer apply.

Ray Kurzweil then muddled things a bit by defining the singularity as the time when the Law of Accelerating Returns has reached such an extreme pace that technological progress is happening at a seemingly-infinite pace, and after which we'll be living in a whole new world. I found that many of today's AI thinkers have stopped using the term, and it's confusing anyway, so I won't use it much here (even though we'll be focusing on that idea throughout).

Finally, while there are many different types or forms of AI since AI is a broad concept, the critical categories we need to think about are based on an AI's caliber. There are three major AI caliber categories:

AI Caliber 1) Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI):Sometimes referred to as Weak AI, Artificial Narrow Intelligence is AI that specializes in one area. There's AI that can beat the world chess champion in chess, but that's the only thing it does. Ask it to figure out a better way to store data on a hard drive, and it'll look at you blankly.

AI Caliber 2) Artificial General Intelligence (AGI):Sometimes referred to as Strong AI, or Human-Level AI, Artificial General Intelligence refers to a computer that is as smart as a human across the board—a machine that can perform any intellectual task that a human being can. Creating an AGI is a much harder task than creating an ANI, and we're yet to do it. Professor Linda Gottfredson describes intelligence as "a very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly, and learn from experience." An AGI would be able to do all of those things as easily as you can.

AI Caliber 3) Artificial Superintelligence (ASI): Oxford philosopher and leading AI thinker Nick Bostrom defines superintelligence as "an intellect that is much smarter than the best human brains in practically every field, including scientific creativity, general wisdom and social skills." Artificial Superintelligence ranges from a computer that's just a little smarter than a human to one that's trillions of times smarter—across the board. ASI is the reason the topic of AI is such a spicy meatball and why the words immortality and extinction will both appear in these posts multiple times.

As of now, humans have conquered the lowest caliber of AI—ANI—in many ways, and it's everywhere. The AI Revolution is the road from ANI, through AGI, to ASI—a road we may or may not survive but that, either way, will change everything.

Let's take a close look at what the leading thinkers in the field believe this road looks like and why this revolution might happen way sooner than you might think:

But while ANI doesn't have the capability to cause an existential threat, we should see this increasingly large and complex ecosystem of relatively-harmless ANI as a precursor of the world-altering hurricane that's on the way. Each new ANI innovation quietly adds another brick onto the road to AGI and ASI. Or as Aaron Saenz sees it, our world's ANI systems "are like the amino acids in the early Earth's primordial ooze"—the inanimate stuff of life that, one unexpected day, woke up.

What's interesting is that the hard parts of trying to build an AGI (a computer as smart as humans in general, not just at one narrow specialty) are not intuitively what you'd think they are. Build a computer that can multiply two ten-digit numbers in a split second—incredibly easy. Build one that can look at a dog and answer whether it's a dog or a cat—spectacularly difficult. Make AI that can beat any human in chess? Done. Make one that can read a paragraph from a six-year-old's picture book and not just recognize the words but understand the meaning of them? Google is currently spending billions of dollars trying to do it. Hard things—like calculus, financial market strategy, and language translation—are mind-numbingly easy for a computer, while easy things—like vision, motion, movement, and perception—are insanely hard for it. Or, as computer scientist Donald Knuth puts it, "AI has by now succeeded in doing essentially everything that requires 'thinking' but has failed to do most of what people and animals do 'without thinking.'"

What you quickly realize when you think about this is that those things that seem easy to us are actually unbelievably complicated, and they only seem easy because those skills have been optimized in us (and most animals) by hundreds of million years of animal evolution. When you reach your hand up toward an object, the muscles, tendons, and bones in your shoulder, elbow, and wrist instantly perform a long series of physics operations, in conjunction with your eyes, to allow you to move your hand in a straight line through three dimensions. It seems effortless to you because you have perfected software in your brain for doing it. Same idea goes for why it's not that malware is dumb for not being able to figure out the slanty word recognition test when you sign up for a new account on a site—it's that your brain is super impressive for being able to.

On the other hand, multiplying big numbers or playing chess are new activities for biological creatures and we haven't had any time to evolve a proficiency at them, so a computer doesn't need to work too hard to beat us. Think about it—which would you rather do, build a program that could multiply big numbers or one that could understand the essence of a B well enough that it you could show it a B in any one of thousands of unpredictable fonts or handwriting and it could instantly know it was a B?

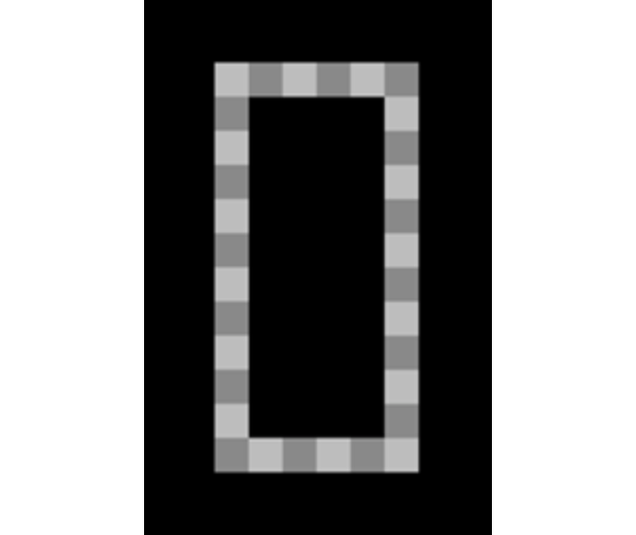

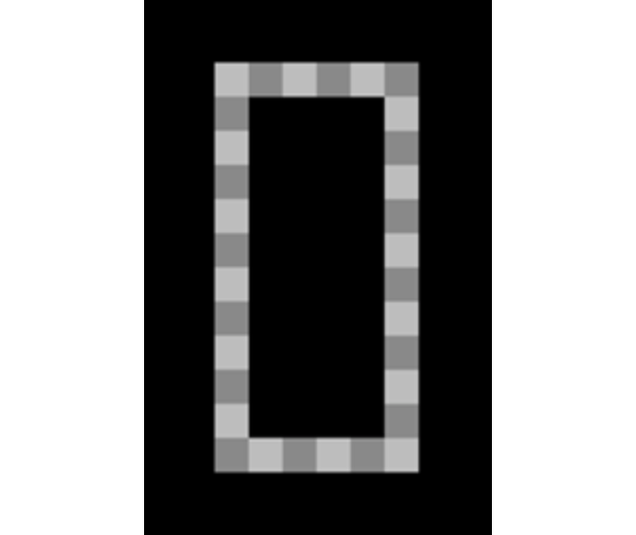

One fun example—when you look at this, you and a computer both can figure out that it's a rectangle with two distinct shades, alternating:

Tied so far. But if you pick up the black and reveal the whole image…

…you have no problem giving a full description of the various opaque and translucent cylinders, slats, and 3-D corners, but the computer would fail miserably. It would describe what it sees—a variety of two-dimensional shapes in several different shades—which is actually what's there. Your brain is doing a ton of fancy shit to interpret the implied depth, shade-mixing, and room lighting the picture is trying to portray. And looking at the picture below, a computer sees a two-dimensional white, black, and gray collage, while you easily see what it really is—a photo of an entirely-black, 3-D rock:

Credit: Matthew Lloyd

And everything we just mentioned is still only taking in stagnant information and processing it. To be human-level intelligent, a computer would have to understand things like the difference between subtle facial expressions, the distinction between being pleased, relieved, content, satisfied, and glad, and why Braveheartwas great but The Patriot was terrible.

Daunting.

So how do we get there?

One way to express this capacity is in the total calculations per second (cps) the brain could manage, and you could come to this number by figuring out the maximum cps of each structure in the brain and then adding them all together.

Ray Kurzweil came up with a shortcut by taking someone's professional estimate for the cps of one structure and that structure's weight compared to that of the whole brain and then multiplying proportionally to get an estimate for the total. Sounds a little iffy, but he did this a bunch of times with various professional estimates of different regions, and the total always arrived in the same ballpark—around 1016, or 10 quadrillion cps.

Currently, the world's fastest supercomputer, China's Tianhe-2, has actually beaten that number, clocking in at about 34 quadrillion cps. But Tianhe-2 is also a dick, taking up 720 square meters of space, using 24 megawatts of power (the brain runs on just 20 watts), and costing $390 million to build. Not especially applicable to wide usage, or even most commercial or industrial usage yet.

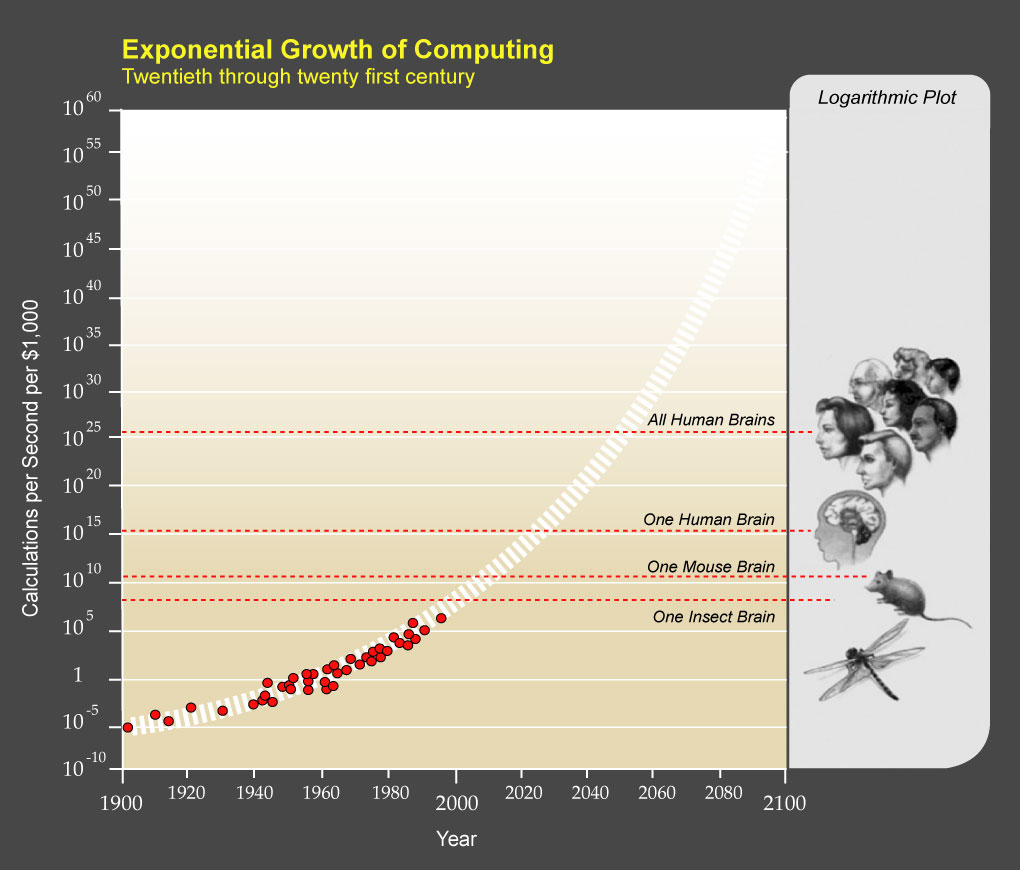

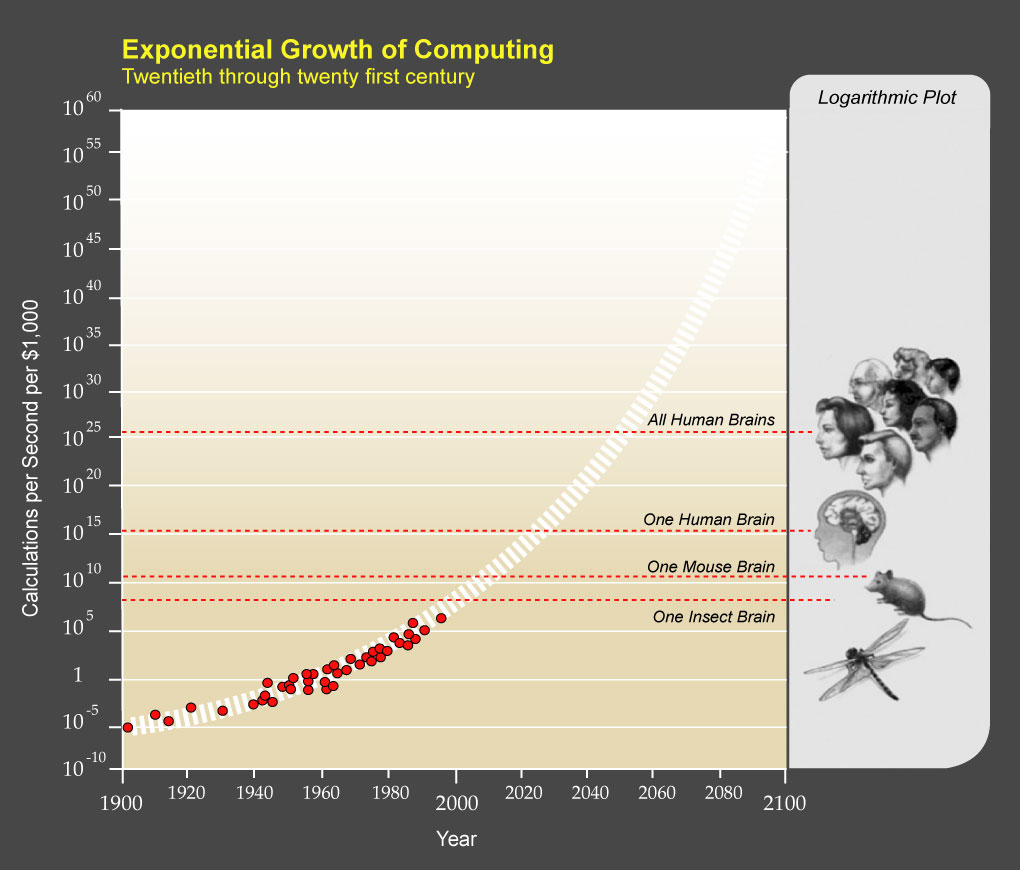

Kurzweil suggests that we think about the state of computers by looking at how many cps you can buy for $1,000. When that number reaches human-level—10 quadrillion cps—then that'll mean AGI could become a very real part of life.

Moore's Law is a historically-reliable rule that the world's maximum computing power doubles approximately every two years, meaning computer hardware advancement, like general human advancement through history, grows exponentially. Looking at how this relates to Kurzweil's cps/$1,000 metric, we're currently at about 10 trillion cps/$1,000, right on pace with this graph's predicted trajectory:

So the world's $1,000 computers are now beating the mouse brain and they're at about a thousandth of human level. This doesn't sound like much until you remember that we were at about a trillionth of human level in 1985, a billionth in 1995, and a millionth in 2005. Being at a thousandth in 2015 puts us right on pace to get to an affordable computer by 2025 that rivals the power of the brain.

So on the hardware side, the raw power needed for AGI is technically available now, in China, and we'll be ready for affordable, widespread AGI-caliber hardware within 10 years. But raw computational power alone doesn't make a computer generally intelligent—the next question is, how do we bring human-level intelligence to all that power?

The science world is working hard on reverse engineering the brain to figure out how evolution made such a rad thing— optimistic estimates say we can do this by 2030. Once we do that, we'll know all the secrets of how the brain runs so powerfully and efficiently and we can draw inspiration from it and steal its innovations. One example of computer architecture that mimics the brain is the artificial neural network. It starts out as a network of transistor "neurons," connected to each other with inputs and outputs, and it knows nothing—like an infant brain. The way it "learns" is it tries to do a task, say handwriting recognition, and at first, its neural firings and subsequent guesses at deciphering each letter will be completely random. But when it's told it got something right, the transistor connections in the firing pathways that happened to create that answer are strengthened; when it's told it was wrong, those pathways' connections are weakened. After a lot of this trial and feedback, the network has, by itself, formed smart neural pathways and the machine has become optimized for the task. The brain learns a bit like this but in a more sophisticated way, and as we continue to study the brain, we're discovering ingenious new ways to take advantage of neural circuitry.

More extreme plagiarism involves a strategy called "whole brain emulation," where the goal is to slice a real brain into thin layers, scan each one, use software to assemble an accurate reconstructed 3-D model, and then implement the model on a powerful computer. We'd then have a computer officially capable of everything the brain is capable of—it would just need to learn and gather information. If engineers get really good, they'd be able to emulate a real brain with such exact accuracy that the brain's full personality and memory would be intact once the brain architecture has been uploaded to a computer. If the brain belonged to Jim right before he passed away, the computer would now wake up as Jim (?), which would be a robust human-level AGI, and we could now work on turning Jim into an unimaginably smart ASI, which he'd probably be really excited about.

How far are we from achieving whole brain emulation? Well so far, we've not yet just recently been able to emulate a 1mm-long flatworm brain, which consists of just 302 total neurons. The human brain contains 100 billion. If that makes it seem like a hopeless project, remember the power of exponential progress—now that we've conquered the tiny worm brain, an ant might happen before too long, followed by a mouse, and suddenly this will seem much more plausible.

Here's something we know. Building a computer as powerful as the brain is possible—our own brain's evolution is proof. And if the brain is just too complex for us to emulate, we could try to emulate evolution instead. The fact is, even if we can emulate a brain, that might be like trying to build an airplane by copying a bird's wing-flapping motions—often, machines are best designed using a fresh, machine-oriented approach, not by mimicking biology exactly.

So how can we simulate evolution to build an AGI? The method, called "genetic algorithms," would work something like this: there would be a performance-and-evaluation process that would happen again and again (the same way biological creatures "perform" by living life and are "evaluated" by whether they manage to reproduce or not). A group of computers would try to do tasks, and the most successful ones would be bred with each other by having half of each of their programming merged together into a new computer. The less successful ones would be eliminated. Over many, many iterations, this natural selection process would produce better and better computers. The challenge would be creating an automated evaluation and breeding cycle so this evolution process could run on its own.

The downside of copying evolution is that evolution likes to take a billion years to do things and we want to do this in a few decades.

But we have a lot of advantages over evolution. First, evolution has no foresight and works randomly—it produces more unhelpful mutations than helpful ones, but we would control the process so it would only be driven by beneficial glitches and targeted tweaks. Secondly, evolution doesn't aim for anything, including intelligence—sometimes an environment might even select against higher intelligence (since it uses a lot of energy). We, on the other hand, could specifically direct this evolutionary process toward increasing intelligence. Third, to select for intelligence, evolution has to innovate in a bunch of other ways to facilitate intelligence—like revamping the ways cells produce energy—when we can remove those extra burdens and use things like electricity. It's no doubt we'd be much, much faster than evolution—but it's still not clear whether we'll be able to improve upon evolution enough to make this a viable strategy.

The idea is that we'd build a computer whose two major skills would be doing research on AI and coding changes into itself—allowing it to not only learn but to improve its own architecture. We'd teach computers to be computer scientists so they could bootstrap their own development. And that would be their main job—figuring out how to make themselves smarter. More on this later.

1) Exponential growth is intense and what seems like a snail's pace of advancement can quickly race upwards. This GIF illustrates the concept nicely.

2) When it comes to software, progress can seem slow, but then one epiphany can instantly change the rate of advancement (kind of like the way science, during the time humans thought the universe was geocentric, was having difficulty calculating how the universe worked, but then the discovery that it was heliocentric suddenly made everything much easier). Or, when it comes to something like a computer that improves itself, we might seem far away but actually be just one tweak of the system away from having it become 1,000 times more effective and zooming upward to human-level intelligence.

At some point, we'll have achieved AGI—computers with human-level general intelligence. Just a bunch of people and computers living together in equality.

Oh actually not at all.

The thing is, an AGI with an identical level of intelligence and computational capacity as a human would still have significant advantages over humans. Like:

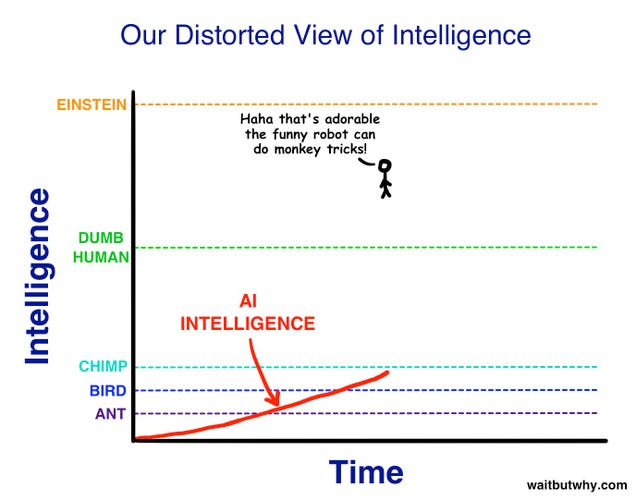

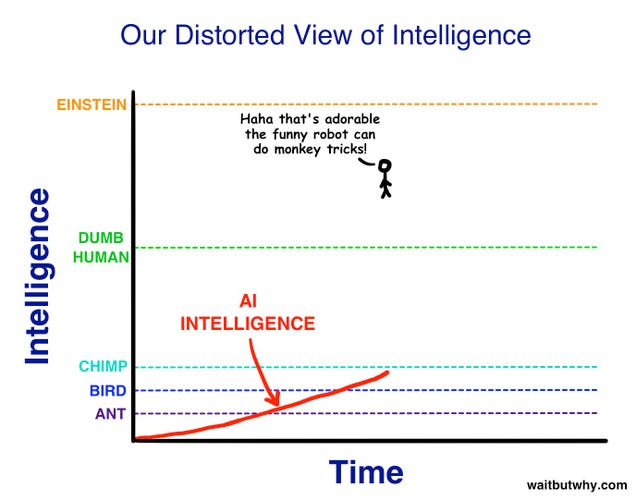

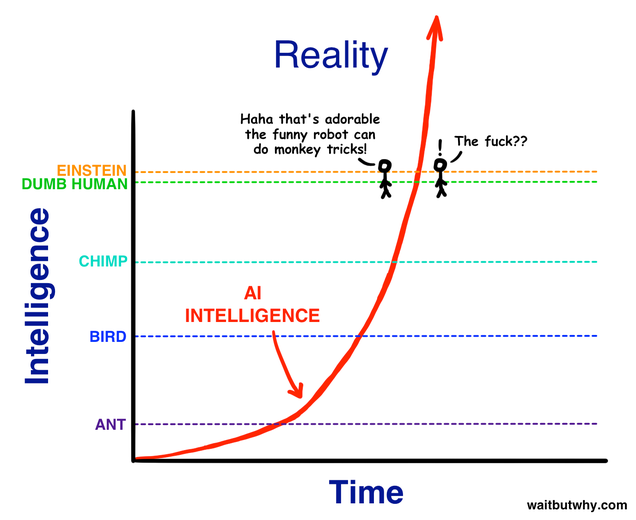

This may shock the shit out of us when it happens. The reason is that from our perspective, A) while the intelligence of different kinds of animals varies, the main characteristic we're aware of about any animal's intelligence is that it's far lower than ours, and B) we view the smartest humans as WAY smarter than the dumbest humans. Kind of like this:

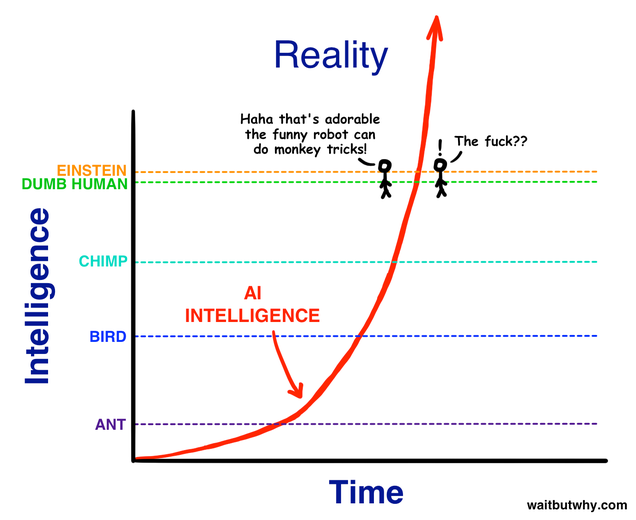

So as AI zooms upward in intelligence toward us, we'll see it as simply becoming smarter, for an animal. Then, when it hits the lowest capacity of humanity—Nick Bostrom uses the term "the village idiot"—we'll be like, "Oh wow, it's like a dumb human. Cute!" The only thing is, in the grand spectrum of intelligence, all humans, from the village idiot to Einstein, are within a very small range—so just after hitting village idiot-level and being declared an AGI, it'll suddenly be smarter than Einstein and we won't know what hit us:

And what happens…after that?

Anyway, as I said above, most of our current models for getting to AGI involve the AI getting there by self-improvement. And once it gets to AGI, even systems that formed and grew through methods that didn't involve self-improvement would now be smart enough to begin self-improving if they wanted to. ( Much more on what it means for a computer to "want" to do something in the Part 2 post.)

And here's where we get to an intense concept:recursive self-improvement. It works like this—

An AI system at a certain level—let's say human village idiot—is programmed with the goal of improving its own intelligence. Once it does, it's smarter—maybe at this point it's at Einstein's level—so now when it works to improve its intelligence, with an Einstein-level intellect, it has an easier time and it can make bigger leaps. These leaps make it much smarter than any human, allowing it to make even bigger leaps. As the leaps grow larger and happen more rapidly, the AGI soars upwards in intelligence and soon reaches the superintelligent level of an ASI system. This is called an Intelligence Explosion (This term was first used by one of history's great AI thinkers, Irving John Good, in 1965), and it's the ultimate example of The Law of Accelerating Returns.

There is some debate about how soon AI will reach human-level general intelligence—the median year on a survey of hundreds of scientists about when they believed we'd be more likely than not to have reached AGI was 2040—that's only 25 years from now, which doesn't sound that huge until you consider that many of the thinkers in this field think it's likely that the progression from AGI to ASI happens very quickly. Like—this could happen:

It takes decades for the first AI system to reach low-level general intelligence, but it finally happens. A computer is able to understand the world around it as well as a human four-year-old. Suddenly, within an hour of hitting that milestone, the system pumps out the grand theory of physics that unifies general relativity and quantum mechanics, something no human has been able to definitively do. 90 minutes after that, the AI has become an ASI, 170,000 times more intelligent than a human.

Superintelligence of that magnitude is not something we can remotely grasp, any more than a bumblebee can wrap its head around Keynesian Economics. In our world, smart means a 130 IQ and stupid means an 85 IQ—we don't have a word for an IQ of 12,952.

What we do know is that humans' utter dominance on this Earth suggests a clear rule: with intelligence comes power. Which means an ASI, when we create it, will be the most powerful being in the history of life on Earth, and all living things, including humans, will be entirely at its whim—and this might happen in the next few decades.

If our meager brains were able to invent wifi, then something 100 or 1,000 or 1 billion times smarter than we are should have no problem controlling the positioning of each and every atom in the world in any way it likes, at any time—everything we consider magic, every power we imagine a supreme God to have will be as mundane an activity for the ASI as flipping on a light switch is for us. Creating the technology to reverse human aging, curing disease and hunger and even mortality, reprogramming the weather to protect the future of life on Earth—all suddenly possible. Also possible is the immediate end of all life on Earth. As far as we're concerned, if an ASI comes to being, there is now an omnipotent God on Earth—and the all-important question for us is:

Source: Waitbuywhy

The AI Revolution: How Far Away Are Our Robot Overlords?

DFRobot

Mar 11 2015 260878

Imagine taking a time machine back to 1750—a time when the world was in a permanent power outage, long-distance communication meant either yelling loudly or firing a cannon in the air, and all transportation ran on hay. When you get there, you retrieve a dude, bring him to 2015, and then walk him around and watch him react to everything.

It's impossible for us to understand what it would be like for him to see shiny capsules racing by on a highway, talk to people who had been on the other side of the ocean earlier in the day, watch sports that were being played 1,000 miles away, hear a musical performance that happened 50 years ago, and play with my magical wizard rectangle that he could use to capture a real-life image or record a living moment, generate a map with a paranormal moving blue dot that shows him where he is, look at someone's face and chat with them even though they're on the other side of the country, and worlds of other inconceivable sorcery. This is all before you show him the internet or explain things like the International Space Station, the Large Hadron Collider, nuclear weapons, or general relativity.

This experience for him wouldn't be surprising or shocking or even mind-blowing—those words aren't big enough. He might actually die.

The Far Future—Coming Soon

But here's the interesting thing—if he then went back to 1750 and got jealous that we got to see his reaction and decided he wanted to try the same thing, he'd take the time machine and go back the same distance, get someone from around the year 1500, bring him to 1750, and show him everything. And the 1500 guy would be shocked by a lot of things—but he wouldn't die. It would be far less of an insane experience for him, because while 1500 and 1750 were very different, they were muchless different than 1750 to 2015. The 1500 guy would learn some mind-bending shit about space and physics, he'd be impressed with how committed Europe turned out to be with that new imperialism fad, and he'd have to do some major revisions of his world map conception. But watching everyday life go by in 1750—transportation, communication, etc.—definitely wouldn't make him die.No, in order for the 1750 guy to have as much fun as we had with him, he'd have to go much farther back—maybe all the way back to about 12,000 BC, before the First Agricultural Revolution gave rise to the first cities and to the concept of civilization. If someone from a purely hunter-gatherer world—from a time when humans were, more or less, just another animal species—saw the vast human empires of 1750 with their towering churches, their ocean-crossing ships, their concept of being "inside," and their enormous mountain of collective, accumulated human knowledge and discovery—he'd likely die.

And then what if, after dying, he got jealous and wanted to do the same thing. If he went back 12,000 years to 24,000 BC and got a guy and brought him to 12,000 BC, he'd show the guy everything and the guy would be like, "Okay what's your point who cares." For the 12,000 BC guy to have the same fun, he'd have to go back over 100,000 years and get someone he could show fire and language to for the first time.

In order for someone to be transported into the future and die from the level of shock they'd experience, they have to go enough years ahead that a "die level of progress," or a Die Progress Unit (DPU) has been achieved. So a DPU took over 100,000 years in hunter-gatherer times, but at the post-Agricultural Revolution rate, it only took about 12,000 years. The post-Industrial Revolution world has moved so quickly that a 1750 person only needs to go forward a couple hundred years for a DPU to have happened.

This pattern—human progress moving quicker and quicker as time goes on—is what futurist Ray Kurzweil calls human history's Law of Accelerating Returns. This happens because more advanced societies have the ability to progress at a faster rate than less advanced societies—because they're more advanced. 19th century humanity knew more and had better technology than 15th century humanity, so it's no surprise that humanity made far more advances in the 19th century than in the 15th century—15th century humanity was no match for 19th century humanity.

This works on smaller scales too. The movie Back to the Future came out in 1985, and "the past" took place in 1955. In the movie, when Michael J. Fox went back to 1955, he was caught off-guard by the newness of TVs, the prices of soda, the lack of love for shrill electric guitar, and the variation in slang. It was a different world, yes—but if the movie were made today and the past took place in 1985, the movie could have had much more fun with much bigger differences. The character would be in a time before personal computers, internet, or cell phones—today's Marty McFly, a teenager born in the late 90s, would be much more out of place in 1985 than the movie's Marty McFly was in 1955.

This is for the same reason we just discussed—the Law of Accelerating Returns. The average rate of advancement between 1985 and 2015 was higher than the rate between 1955 and 1985—because the former was a more advanced world—so much more change happened in the most recent 30 years than in the prior 30.

So—advances are getting bigger and bigger and happening more and more quickly. This suggests some pretty intense things about our future, right?

Kurzweil suggests that the progress of the entire 20th century would have been achieved in only 20 years at the rate of advancement in the year 2000—in other words, by 2000, the rate of progress was five times faster than the average rate of progress during the 20th century. He believes another 20th century's worth of progress happened between 2000 and 2014 and that another 20th century's worth of progress will happen by 2021, in only seven years. A couple decades later, he believes a 20th century's worth of progress will happen multiple times in the same year, and even later, in less than one month. All in all, because of the Law of Accelerating Returns, Kurzweil believes that the 21st century will achieve 1,000 times the progress of the 20th century.

If Kurzweil and others who agree with him are correct, then we may be as blown away by 2030 as our 1750 guy was by 2015—i.e. the next DPU might only take a couple decades—and the world in 2050 might be so vastly different than today's world that we would barely recognize it.

This isn't science fiction. It's what many scientists smarter and more knowledgeable than you or I firmly believe—and if you look at history, it's what we should logically predict.

So then why, when you hear me say something like "the world 35 years from now might be totally unrecognizable," are you thinking, "Cool….but nahhhhhhh"? Three reasons we're skeptical of outlandish forecasts of the future:

1) When it comes to history, we think in straight lines.

When we imagine the progress of the next 30 years, we look back to the progress of the previous 30 as an indicator of how much will likely happen. When we think about the extent to which the world will change in the 21st century, we just take the 20th century progress and add it to the year 2000. This was the same mistake our 1750 guy made when he got someone from 1500 and expected to blow his mind as much as his own was blown going the same distance ahead.It's most intuitive for us to think linearly, when we should be thinkingexponentially. If someone is being more clever about it, they might predict the advances of the next 30 years not by looking at the previous 30 years, but by taking thecurrent rate of progress and judging based on that. They'd be more accurate, but still way off. In order to think about the future correctly, you need to imagine things moving at a much faster rate than they're moving now.

2) The trajectory of very recent history often tells a distorted story.

First, even a steep exponential curve seems linear when you only look at a tiny slice of it, the same way if you look at a little segment of a huge circle up close, it looks almost like a straight line. Second, exponential growth isn't totally smooth and uniform. Kurzweil explains that progress happens in "S-curves":

1).Slow growth (the early phase of exponential growth)

2).Rapid growth (the late, explosive phase of exponential growth)

3).A leveling off as the particular paradigm matures.

If you look only at very recent history, the part of the S-curve you're on at the moment can obscure your perception of how fast things are advancing. The chunk of time between 1995 and 2007 saw the explosion of the internet, the introduction of Microsoft, Google, and Facebook into the public consciousness, the birth of social networking, and the introduction of cell phones and then smart phones.

That was Phase 2: the growth spurt part of the S. But 2008 to 2015 has been less groundbreaking, at least on the technological front. Someone thinking about the future today might examine the last few years to gauge the current rate of advancement, but that's missing the bigger picture. In fact, a new, huge Phase 2 growth spurt might be brewing right now.

3) Our own experience makes us stubborn old men about the future.

We base our ideas about the world on our personal experience, and that experience has ingrained the rate of growth of the recent past in our heads as "the way things happen." We're also limited by our imagination, which takes our experience and uses it to conjure future predictions—but often, what we know simply doesn't give us the tools to think accurately about the future. (Kurzweil points out that his phone is about a millionth the size of, a millionth the price of, and a thousand times more powerful than his MIT computer was 40 years ago. Good luck trying to figure out where a comparable future advancement in computing would leave us, let alone one far, far more extreme, since the progress grows exponentially.)

When we hear a prediction about the future that contradicts our experience-based notion ofhow things work, our instinct is that the prediction must be naive. If I tell you, later in this post, that you may live to be 150, or 250, or not die at all, your instinct will be, "That's stupid—if there's one thing I know from history, it's that everybody dies." And yes, no one in the past has not died. But no one flew airplanes before airplanes were invented either.

So while nahhhhh might feel right as you read this post, it's probably actually wrong. The fact is, if we're being truly logical and expecting historical patterns to continue, we should conclude that much, much, much more should change in the coming decades than we intuitively expect. Logic also suggests that if the most advanced species on a planet keeps making larger and larger leaps forward at an ever-faster rate, at some point, they'll make a leap so great that it completely alters life as they know it and the perception they have of what it means to be a human—kind of like how evolution kept making great leaps toward intelligence until finally it made such a large leap to the human being that it completely altered what it meant for any creature to live on planet Earth.

And if you spend some time reading about what's going on today in science and technology, you start to see a lot of signs quietly hinting that life as we know it cannot withstand the leap that's coming next.

The Road to Superintelligence

What Is AI?

If you're like me, you used to think Artificial Intelligence was a silly sci-fi concept, but lately you've been hearing it mentioned by serious people, and you don't really quite get it.There are three reasons a lot of people are confused about the term AI:

1) We associate AI with movies. Star Wars. Terminator. 2001: A Space Odyssey. Even the Jetsons. And those are fiction, as are the robot characters. So it makes AI sound a little fictional to us.

2) AI is a broad topic. It ranges from your phone's calculator to self-driving cars to something in the future that might change the world dramatically. AI refers to all of these things, which is confusing.

3) We use AI all the time in our daily lives, but we often don't realize it's AI. John McCarthy, who coined the term "Artificial Intelligence" in 1956, complained that "as soon as it works, no one calls it AI anymore." Because of this phenomenon, AI often sounds like a mythical future prediction more than a reality. At the same time, it makes it sound like a pop concept from the past that never came to fruition. Ray Kurzweil says he hears people say that AI withered in the 1980s, which he compares to "insisting that the Internet died in the dot-com bust of the early 2000s."

So let's clear things up. First, stop thinking of robots. A robot is a container for AI, sometimes mimicking the human form, sometimes not—but the AI itself is the computer inside the robot. AI is the brain, and the robot is its body—if it even has a body. For example, the software and data behind Siri is AI, the woman's voice we hear is a personification of that AI, and there's no robot involved at all.

Secondly, you've probably heard the term "singularity" or "technological singularity." This term has been used in math to describe an asymptote-like situation where normal rules no longer apply. It's been used in physics to describe a phenomenon like an infinitely small, dense black hole or the point we were all squished into right before the Big Bang. Again, situations where the usual rules don't apply. In 1993, Vernor Vinge wrote a famous essay in which he applied the term to the moment in the future when our technology's intelligence exceeds our own—a moment for him when life as we know it will be forever changed and normal rules will no longer apply.

Ray Kurzweil then muddled things a bit by defining the singularity as the time when the Law of Accelerating Returns has reached such an extreme pace that technological progress is happening at a seemingly-infinite pace, and after which we'll be living in a whole new world. I found that many of today's AI thinkers have stopped using the term, and it's confusing anyway, so I won't use it much here (even though we'll be focusing on that idea throughout).

Finally, while there are many different types or forms of AI since AI is a broad concept, the critical categories we need to think about are based on an AI's caliber. There are three major AI caliber categories:

AI Caliber 1) Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI):Sometimes referred to as Weak AI, Artificial Narrow Intelligence is AI that specializes in one area. There's AI that can beat the world chess champion in chess, but that's the only thing it does. Ask it to figure out a better way to store data on a hard drive, and it'll look at you blankly.

AI Caliber 2) Artificial General Intelligence (AGI):Sometimes referred to as Strong AI, or Human-Level AI, Artificial General Intelligence refers to a computer that is as smart as a human across the board—a machine that can perform any intellectual task that a human being can. Creating an AGI is a much harder task than creating an ANI, and we're yet to do it. Professor Linda Gottfredson describes intelligence as "a very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly, and learn from experience." An AGI would be able to do all of those things as easily as you can.

AI Caliber 3) Artificial Superintelligence (ASI): Oxford philosopher and leading AI thinker Nick Bostrom defines superintelligence as "an intellect that is much smarter than the best human brains in practically every field, including scientific creativity, general wisdom and social skills." Artificial Superintelligence ranges from a computer that's just a little smarter than a human to one that's trillions of times smarter—across the board. ASI is the reason the topic of AI is such a spicy meatball and why the words immortality and extinction will both appear in these posts multiple times.

As of now, humans have conquered the lowest caliber of AI—ANI—in many ways, and it's everywhere. The AI Revolution is the road from ANI, through AGI, to ASI—a road we may or may not survive but that, either way, will change everything.

Let's take a close look at what the leading thinkers in the field believe this road looks like and why this revolution might happen way sooner than you might think:

Where We Are Currently—A World Running on ANI

Artificial Narrow Intelligence is machine intelligence that equals or exceeds human intelligence or efficiency at a specific thing. A few examples:- Cars are full of ANI systems, from the computer that figures out when the anti-lock brakes should kick in to the computer that tunes the parameters of the fuel injection systems. Google's self-driving car, which is being tested now, will contain robust ANI systems that allow it to perceive and react to the world around it.

- Your phone is a little ANI factory. When you navigate using your map app, receive tailored music recommendations from Pandora, check tomorrow's weather, talk to Siri, or dozens of other everyday activities, you're using ANI.

- Your email spam filter is a classic type of ANI—it starts off loaded with intelligence about how to figure out what's spam and what's not, and then it learns and tailors its intelligence to you as it gets experience with your particular preferences. The Nest Thermostat does the same thing as it starts to figure out your typical routine and act accordingly.

- You know the whole creepy thing that goes on when you search for a product on Amazon and then you see that as a "recommended for you" product on a different site, or when Facebook somehow knows who it makes sense for you to add as a friend? That's a network of ANI systems, working together to inform each other about who you are and what you like and then using that information to decide what to show you. Same goes for Amazon's "People who bought this also bought…" thing—that's an ANI whose job it is to gather info from the behavior of millions of customers and synthesize that info to cleverly upsell you so you'll buy more things.

- Google Translate is another classic ANI—impressively good at one narrow task. Voice recognition is another, and there are a bunch of apps that use those two ANIs as a tag team, allowing you to speak a sentence in one language and have the phone spit out the same sentence in another.

- When your plane lands, it's not a human that decides which gate it should go to. Just like it's not a human that determined the price of your ticket.

- The world's best Checkers, Chess, Scrabble, Backgammon, and Othello players are now all ANI systems.

- Google search is one large ANI brain with incredibly sophisticated methods for ranking pages and figuring out what to show you in particular. Same goes for Facebook's Newsfeed.

- And those are just in the consumer world. Sophisticated ANI systems are widely used in sectors and industries like military, manufacturing, and finance (algorithmic high-frequency AI traders account for more than half of equity shares traded on US markets), and in expert systems like those that help doctors make diagnoses and, most famously, IBM's Watson, who contained enough facts and understood coy Trebek-speak well enough to soundly beat the most prolific Jeopardy champions.

But while ANI doesn't have the capability to cause an existential threat, we should see this increasingly large and complex ecosystem of relatively-harmless ANI as a precursor of the world-altering hurricane that's on the way. Each new ANI innovation quietly adds another brick onto the road to AGI and ASI. Or as Aaron Saenz sees it, our world's ANI systems "are like the amino acids in the early Earth's primordial ooze"—the inanimate stuff of life that, one unexpected day, woke up.

The Road From ANI to AGI

Why It's So Hard

Nothing will make you appreciate human intelligence like learning about how unbelievably challenging it is to try to create a computer as smart as we are. Building skyscrapers, putting humans in space, figuring out the details of how the Big Bang went down—all far easier than understanding our own brain or how to make something as cool as it. As of now, the human brain is the most complex object in the known universe.What's interesting is that the hard parts of trying to build an AGI (a computer as smart as humans in general, not just at one narrow specialty) are not intuitively what you'd think they are. Build a computer that can multiply two ten-digit numbers in a split second—incredibly easy. Build one that can look at a dog and answer whether it's a dog or a cat—spectacularly difficult. Make AI that can beat any human in chess? Done. Make one that can read a paragraph from a six-year-old's picture book and not just recognize the words but understand the meaning of them? Google is currently spending billions of dollars trying to do it. Hard things—like calculus, financial market strategy, and language translation—are mind-numbingly easy for a computer, while easy things—like vision, motion, movement, and perception—are insanely hard for it. Or, as computer scientist Donald Knuth puts it, "AI has by now succeeded in doing essentially everything that requires 'thinking' but has failed to do most of what people and animals do 'without thinking.'"

What you quickly realize when you think about this is that those things that seem easy to us are actually unbelievably complicated, and they only seem easy because those skills have been optimized in us (and most animals) by hundreds of million years of animal evolution. When you reach your hand up toward an object, the muscles, tendons, and bones in your shoulder, elbow, and wrist instantly perform a long series of physics operations, in conjunction with your eyes, to allow you to move your hand in a straight line through three dimensions. It seems effortless to you because you have perfected software in your brain for doing it. Same idea goes for why it's not that malware is dumb for not being able to figure out the slanty word recognition test when you sign up for a new account on a site—it's that your brain is super impressive for being able to.

On the other hand, multiplying big numbers or playing chess are new activities for biological creatures and we haven't had any time to evolve a proficiency at them, so a computer doesn't need to work too hard to beat us. Think about it—which would you rather do, build a program that could multiply big numbers or one that could understand the essence of a B well enough that it you could show it a B in any one of thousands of unpredictable fonts or handwriting and it could instantly know it was a B?

One fun example—when you look at this, you and a computer both can figure out that it's a rectangle with two distinct shades, alternating:

Tied so far. But if you pick up the black and reveal the whole image…

…you have no problem giving a full description of the various opaque and translucent cylinders, slats, and 3-D corners, but the computer would fail miserably. It would describe what it sees—a variety of two-dimensional shapes in several different shades—which is actually what's there. Your brain is doing a ton of fancy shit to interpret the implied depth, shade-mixing, and room lighting the picture is trying to portray. And looking at the picture below, a computer sees a two-dimensional white, black, and gray collage, while you easily see what it really is—a photo of an entirely-black, 3-D rock:

Credit: Matthew Lloyd

And everything we just mentioned is still only taking in stagnant information and processing it. To be human-level intelligent, a computer would have to understand things like the difference between subtle facial expressions, the distinction between being pleased, relieved, content, satisfied, and glad, and why Braveheartwas great but The Patriot was terrible.

Daunting.

So how do we get there?

First Key to Creating AGI: Increasing Computational Power

One thing that definitely needs to happen for AGI to be a possibility is an increase in the power of computer hardware. If an AI system is going to be as intelligent as the brain, it'll need to equal the brain's raw computing capacity.One way to express this capacity is in the total calculations per second (cps) the brain could manage, and you could come to this number by figuring out the maximum cps of each structure in the brain and then adding them all together.

Ray Kurzweil came up with a shortcut by taking someone's professional estimate for the cps of one structure and that structure's weight compared to that of the whole brain and then multiplying proportionally to get an estimate for the total. Sounds a little iffy, but he did this a bunch of times with various professional estimates of different regions, and the total always arrived in the same ballpark—around 1016, or 10 quadrillion cps.

Currently, the world's fastest supercomputer, China's Tianhe-2, has actually beaten that number, clocking in at about 34 quadrillion cps. But Tianhe-2 is also a dick, taking up 720 square meters of space, using 24 megawatts of power (the brain runs on just 20 watts), and costing $390 million to build. Not especially applicable to wide usage, or even most commercial or industrial usage yet.

Kurzweil suggests that we think about the state of computers by looking at how many cps you can buy for $1,000. When that number reaches human-level—10 quadrillion cps—then that'll mean AGI could become a very real part of life.

Moore's Law is a historically-reliable rule that the world's maximum computing power doubles approximately every two years, meaning computer hardware advancement, like general human advancement through history, grows exponentially. Looking at how this relates to Kurzweil's cps/$1,000 metric, we're currently at about 10 trillion cps/$1,000, right on pace with this graph's predicted trajectory:

So the world's $1,000 computers are now beating the mouse brain and they're at about a thousandth of human level. This doesn't sound like much until you remember that we were at about a trillionth of human level in 1985, a billionth in 1995, and a millionth in 2005. Being at a thousandth in 2015 puts us right on pace to get to an affordable computer by 2025 that rivals the power of the brain.

So on the hardware side, the raw power needed for AGI is technically available now, in China, and we'll be ready for affordable, widespread AGI-caliber hardware within 10 years. But raw computational power alone doesn't make a computer generally intelligent—the next question is, how do we bring human-level intelligence to all that power?

Second Key to Creating AGI: Making it Smart

This is the icky part. The truth is, no one really knows how to make it smart—we're still debating how to make a computer human-level intelligent and capable of knowing what a dog and a weird-written B and a mediocre movie is. But there are a bunch of far-fetched strategies out there and at some point, one of them will work. Here are the three most common strategies I came across:1) Plagiarize the brain.

This is like scientists toiling over how that kid who sits next to them in class is so smart and keeps doing so well on the tests, and even though they keep studying diligently, they can't do nearly as well as that kid, and then they finally decide "k fuck it I'm just gonna copy that kid's answers." It makes sense—we're stumped trying to build a super-complex computer, and there happens to be a perfect prototype for one in each of our heads.The science world is working hard on reverse engineering the brain to figure out how evolution made such a rad thing— optimistic estimates say we can do this by 2030. Once we do that, we'll know all the secrets of how the brain runs so powerfully and efficiently and we can draw inspiration from it and steal its innovations. One example of computer architecture that mimics the brain is the artificial neural network. It starts out as a network of transistor "neurons," connected to each other with inputs and outputs, and it knows nothing—like an infant brain. The way it "learns" is it tries to do a task, say handwriting recognition, and at first, its neural firings and subsequent guesses at deciphering each letter will be completely random. But when it's told it got something right, the transistor connections in the firing pathways that happened to create that answer are strengthened; when it's told it was wrong, those pathways' connections are weakened. After a lot of this trial and feedback, the network has, by itself, formed smart neural pathways and the machine has become optimized for the task. The brain learns a bit like this but in a more sophisticated way, and as we continue to study the brain, we're discovering ingenious new ways to take advantage of neural circuitry.

More extreme plagiarism involves a strategy called "whole brain emulation," where the goal is to slice a real brain into thin layers, scan each one, use software to assemble an accurate reconstructed 3-D model, and then implement the model on a powerful computer. We'd then have a computer officially capable of everything the brain is capable of—it would just need to learn and gather information. If engineers get really good, they'd be able to emulate a real brain with such exact accuracy that the brain's full personality and memory would be intact once the brain architecture has been uploaded to a computer. If the brain belonged to Jim right before he passed away, the computer would now wake up as Jim (?), which would be a robust human-level AGI, and we could now work on turning Jim into an unimaginably smart ASI, which he'd probably be really excited about.

How far are we from achieving whole brain emulation? Well so far, we've not yet just recently been able to emulate a 1mm-long flatworm brain, which consists of just 302 total neurons. The human brain contains 100 billion. If that makes it seem like a hopeless project, remember the power of exponential progress—now that we've conquered the tiny worm brain, an ant might happen before too long, followed by a mouse, and suddenly this will seem much more plausible.

2) Try to make evolution do what it did before but for us this time.

So if we decide the smart kid's test is too hard to copy, we can try to copy the way he studies for the tests instead.Here's something we know. Building a computer as powerful as the brain is possible—our own brain's evolution is proof. And if the brain is just too complex for us to emulate, we could try to emulate evolution instead. The fact is, even if we can emulate a brain, that might be like trying to build an airplane by copying a bird's wing-flapping motions—often, machines are best designed using a fresh, machine-oriented approach, not by mimicking biology exactly.

So how can we simulate evolution to build an AGI? The method, called "genetic algorithms," would work something like this: there would be a performance-and-evaluation process that would happen again and again (the same way biological creatures "perform" by living life and are "evaluated" by whether they manage to reproduce or not). A group of computers would try to do tasks, and the most successful ones would be bred with each other by having half of each of their programming merged together into a new computer. The less successful ones would be eliminated. Over many, many iterations, this natural selection process would produce better and better computers. The challenge would be creating an automated evaluation and breeding cycle so this evolution process could run on its own.

The downside of copying evolution is that evolution likes to take a billion years to do things and we want to do this in a few decades.

But we have a lot of advantages over evolution. First, evolution has no foresight and works randomly—it produces more unhelpful mutations than helpful ones, but we would control the process so it would only be driven by beneficial glitches and targeted tweaks. Secondly, evolution doesn't aim for anything, including intelligence—sometimes an environment might even select against higher intelligence (since it uses a lot of energy). We, on the other hand, could specifically direct this evolutionary process toward increasing intelligence. Third, to select for intelligence, evolution has to innovate in a bunch of other ways to facilitate intelligence—like revamping the ways cells produce energy—when we can remove those extra burdens and use things like electricity. It's no doubt we'd be much, much faster than evolution—but it's still not clear whether we'll be able to improve upon evolution enough to make this a viable strategy.

3) Make this whole thing the computer's problem, not ours.

This is when scientists get desperate and try to program the test to take itself. But it might be the most promising method we have.The idea is that we'd build a computer whose two major skills would be doing research on AI and coding changes into itself—allowing it to not only learn but to improve its own architecture. We'd teach computers to be computer scientists so they could bootstrap their own development. And that would be their main job—figuring out how to make themselves smarter. More on this later.

All of This Could Happen Soon

Rapid advancements in hardware and innovative experimentation with software are happening simultaneously, and AGI could creep up on us quickly and unexpectedly for two main reasons:1) Exponential growth is intense and what seems like a snail's pace of advancement can quickly race upwards. This GIF illustrates the concept nicely.

2) When it comes to software, progress can seem slow, but then one epiphany can instantly change the rate of advancement (kind of like the way science, during the time humans thought the universe was geocentric, was having difficulty calculating how the universe worked, but then the discovery that it was heliocentric suddenly made everything much easier). Or, when it comes to something like a computer that improves itself, we might seem far away but actually be just one tweak of the system away from having it become 1,000 times more effective and zooming upward to human-level intelligence.

The Road From AGI to ASI

At some point, we'll have achieved AGI—computers with human-level general intelligence. Just a bunch of people and computers living together in equality.

Oh actually not at all.

The thing is, an AGI with an identical level of intelligence and computational capacity as a human would still have significant advantages over humans. Like:

Hardware

- Speed. The brain's neurons max out at around 200 Hz, while today's microprocessors (which are much slower than they will be when we reach AGI) run at 2 GHz, or 10 million times faster than our neurons. And the brain's internal communications, which can move at about 120 m/s, are horribly outmatched by a computer's ability to communicate optically at the speed of light.

- Size and storage. The brain is locked into its size by the shape of our skulls, and it couldn't get much bigger anyway, or the 120 m/s internal communications would take too long to get from one brain structure to another. Computers can expand to any physical size, allowing far more hardware to be put to work, a much larger working memory (RAM), and a longterm memory (hard drive storage) that has both far greater capacity and precision than our own.

- Reliability and durability. It's not only the memories of a computer that would be more precise. Computer transistors are more accurate than biological neurons, and they're less likely to deteriorate (and can be repaired or replaced if they do). Human brains also get fatigued easily, while computers can run nonstop, at peak performance, 24/7.

- Editability, upgradability, and a wider breadth of possibility. Unlike the human brain, computer software can receive updates and fixes and can be easily experimented on. The upgrades could also span to areas where human brains are weak. Human vision software is superbly advanced, while its complex engineering capability is pretty low-grade. Computers could match the human on vision software but could also become equally optimized in engineering and any other area.

- Collective capability. Humans crush all other species at building a vast collective intelligence. Beginning with the development of language and the forming of large, dense communities, advancing through the inventions of writing and printing, and now intensified through tools like the internet, humanity's collective intelligence is one of the major reasons we've been able to get so far ahead of all other species. And computers will be way better at it than we are. A worldwide network of AI running a particular program could regularly sync with itself so that anything any one computer learned would be instantly uploaded to all other computers. The group could also take on one goal as a unit, because there wouldn't necessarily be dissenting opinions and motivations and self-interest, like we have within the human population.

Software:

- Editability, upgradability, and a wider breadth of possibility. Unlike the human brain, computer software can receive updates and fixes and can be easily experimented on. The upgrades could also span to areas where human brains are weak. Human vision software is superbly advanced, while its complex engineering capability is pretty low-grade. Computers could match the human on vision software but could also become equally optimized in engineering and any other area.

- Collective capability. Humans crush all other species at building a vast collective intelligence. Beginning with the development of language and the forming of large, dense communities, advancing through the inventions of writing and printing, and now intensified through tools like the internet, humanity's collective intelligence is one of the major reasons we've been able to get so far ahead of all other species. And computers will be way better at it than we are. A worldwide network of AI running a particular program could regularly sync with itself so that anything any one computer learned would be instantly uploaded to all other computers. The group could also take on one goal as a unit, because there wouldn't necessarily be dissenting opinions and motivations and self-interest, like we have within the human population.

This may shock the shit out of us when it happens. The reason is that from our perspective, A) while the intelligence of different kinds of animals varies, the main characteristic we're aware of about any animal's intelligence is that it's far lower than ours, and B) we view the smartest humans as WAY smarter than the dumbest humans. Kind of like this:

So as AI zooms upward in intelligence toward us, we'll see it as simply becoming smarter, for an animal. Then, when it hits the lowest capacity of humanity—Nick Bostrom uses the term "the village idiot"—we'll be like, "Oh wow, it's like a dumb human. Cute!" The only thing is, in the grand spectrum of intelligence, all humans, from the village idiot to Einstein, are within a very small range—so just after hitting village idiot-level and being declared an AGI, it'll suddenly be smarter than Einstein and we won't know what hit us:

And what happens…after that?

An Intelligence Explosion

I hope you enjoyed normal time, because this is when this topic gets unnormal and scary, and it's gonna stay that way from here forward. I want to pause here to remind you that every single thing I'm going to say is real—real science and real forecasts of the future from a large array of the most respected thinkers and scientists. Just keep remembering that.Anyway, as I said above, most of our current models for getting to AGI involve the AI getting there by self-improvement. And once it gets to AGI, even systems that formed and grew through methods that didn't involve self-improvement would now be smart enough to begin self-improving if they wanted to. ( Much more on what it means for a computer to "want" to do something in the Part 2 post.)

And here's where we get to an intense concept:recursive self-improvement. It works like this—

An AI system at a certain level—let's say human village idiot—is programmed with the goal of improving its own intelligence. Once it does, it's smarter—maybe at this point it's at Einstein's level—so now when it works to improve its intelligence, with an Einstein-level intellect, it has an easier time and it can make bigger leaps. These leaps make it much smarter than any human, allowing it to make even bigger leaps. As the leaps grow larger and happen more rapidly, the AGI soars upwards in intelligence and soon reaches the superintelligent level of an ASI system. This is called an Intelligence Explosion (This term was first used by one of history's great AI thinkers, Irving John Good, in 1965), and it's the ultimate example of The Law of Accelerating Returns.

There is some debate about how soon AI will reach human-level general intelligence—the median year on a survey of hundreds of scientists about when they believed we'd be more likely than not to have reached AGI was 2040—that's only 25 years from now, which doesn't sound that huge until you consider that many of the thinkers in this field think it's likely that the progression from AGI to ASI happens very quickly. Like—this could happen:

It takes decades for the first AI system to reach low-level general intelligence, but it finally happens. A computer is able to understand the world around it as well as a human four-year-old. Suddenly, within an hour of hitting that milestone, the system pumps out the grand theory of physics that unifies general relativity and quantum mechanics, something no human has been able to definitively do. 90 minutes after that, the AI has become an ASI, 170,000 times more intelligent than a human.

Superintelligence of that magnitude is not something we can remotely grasp, any more than a bumblebee can wrap its head around Keynesian Economics. In our world, smart means a 130 IQ and stupid means an 85 IQ—we don't have a word for an IQ of 12,952.

What we do know is that humans' utter dominance on this Earth suggests a clear rule: with intelligence comes power. Which means an ASI, when we create it, will be the most powerful being in the history of life on Earth, and all living things, including humans, will be entirely at its whim—and this might happen in the next few decades.

If our meager brains were able to invent wifi, then something 100 or 1,000 or 1 billion times smarter than we are should have no problem controlling the positioning of each and every atom in the world in any way it likes, at any time—everything we consider magic, every power we imagine a supreme God to have will be as mundane an activity for the ASI as flipping on a light switch is for us. Creating the technology to reverse human aging, curing disease and hunger and even mortality, reprogramming the weather to protect the future of life on Earth—all suddenly possible. Also possible is the immediate end of all life on Earth. As far as we're concerned, if an ASI comes to being, there is now an omnipotent God on Earth—and the all-important question for us is:

Will it be a nice God?

That's the topic of Part 2 of this post.Source: Waitbuywhy